Blurb: Pleasure Dome

Bad Boys: What JT Leroy Knew (About Being Fucked Up)

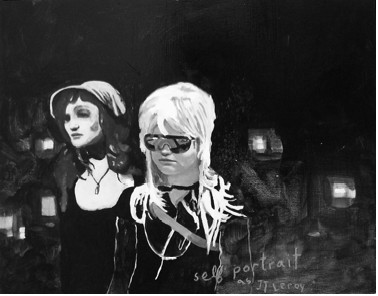

"Self portrait as JT Leroy," Margaux Williamson, 2006

In Fond Memory of Jeremiah Terminator LeRoy, 1994-2006

PROGRAMME:

Box (63), Steve Reinke, Canada, 1995, video, 3 min.

The End of My Death (64), Steve Reinke, Canada, 1995, video, 2 min.

In these two tapes from The Hundred Videos, Reinke considers how a figure as monstrously queer as Jeffrey Dahmer was packaged by the mainstream media, how his identity and story were structured for maximum shock and titillation. In Box , Dahmer's anguished father is forced by the most influential woman in the world to reveal the horrific but oh-so-juicy punchline to his meandering story while in The End of My Death , Dahmer - or perhaps his ghost - reflects on his fraught public persona.

A Rock and a Hard Place , Joshua Thorson, USA, 2006, video, 23 min.

"This semi-narrative re-enactment video, a closed system compiled from bits of newspaper articles, a novel, an exposé, and an Oprah special, follows real events that took place between the years 1993 and 1995 between a young boy who writes a best-selling memoir of his abusive upbringing, his foster mother, and a famous gay novelist, whom he has never met in person. When a meddling reporter begins to snoop around, the triad is thrown into confusion." (Joshua Thorson)

Who I Am and What I Want , David Shrigley & Chris Shepherd, UK, 2005, video, 7 min.

In a breathless cavalcade of perversion, our protagonist explains what makes him tick and what drives him to do the nasty things he does. Absurd and disturbing, the transgressions he lists would be impossible to translate into the quasi-tasteful confessions that Oprah hungers for: This animalistic, stick-figure "I" says too much and gets everyone covered in shit. He almost resembles Divine in John Waters's Female Trouble , so crazed he risks exterminating the audience to prove how monstrous he can be (but then there'd be no one left to hear how filthy he is).

A Family Finds Entertainment , Ryan Trecartin, USA, 2004, video, 41 min.

A Family Finds Entertainment presents a world molded and mutated by television and digital media, where the never-ending drive for entertainment has rendered everyone an attention deficit-disordered circus freak. It is abrasive, garish and occasionally boring -the nuttiness is both exhilarating and exhausting. Characters speak in clichés and catch-phrases, and have no shame about their squalid excess and their desperate hamminess - their bad acting the mark of rough-hewn authenticity and the unbridled lust for the spotlight. Trecartin's universe here is pure, cruel artifice and no emotion; he burlesques familiar narratives of the suicidal gay teen rather than soliciting our identification.

I'm Ready for My Close-Up, Ms. Winfrey

"[I]t was easy for me to go on for pages about things that never happened [...] Charlotte, the spider in Charlotte's Web , knew what she was talking about when she said that humans were gullible, that they believed anything they saw in print. My teachers were living testimony to that. The problem was that the more I lied, the more desperate I felt about the truth of the situation that I lived in."

- Anthony Godby Johnson, A Rock and a Hard Place , p. 54.

This programme is haunted by the ghost of star author JT Leroy, who embodies some of the weirdest aspects of the overlap of queer and celebrity cultures. He was revealed to be a hoax perpetuated over a decade, the fantastic invention of a struggling punk musician and writer named Laura Albert who was fifteen years JT's senior. She was the author of the words (on the printed page, in blogs and in e-mails) and the voice on the phone - the primary ways that JT's minions of friends experienced them. These videos tonight cast light on the cultural fixations that allowed JT to happen: the very queer connections between celebrity, victimhood, identification and pleasure.

If JT had been born a decade earlier (and were he not so deeply cool), he would have been perfect for the TV talk show circuit. Created in the mid-90s as the personification of all that we love, pity and scorn about fucked-up boys, JT didn't need television - he could make the whole wide world into Oprah's couch. He suffered 31 flavours of oppression so that every potential fan could identify with him, whether stalwarts of transgressive fiction like Dennis Cooper or Mary Gaitskill or stars like Winona Ryder and Courtney Love. JT was a Warholian blank slate that everyone could project their own narratives of suffering, struggle and success onto. He transcended the queer underground and made its stigmas and culture fashionable. Who would have imagined a time when disenfranchised identities - genderqueer, white trash, drug addict, child trannie truckstop prostitute, PWA, abuse survivor, street kid, suicidal etc. - are collected like trading cards? (I still like Susie Bright's label for JT of "lumpen gutter whore child" best.) But did this Southern-fried, waifish spectre make light of the seriousness of these experiences or did JT/Laura merely illuminate the grotesque ways that marginalization has been easily appropriated into consumer capitalism? JT's narrative of oppression and overcoming is as American as apple pie, and anyone, no matter how downtrodden, can be dropped into the endless assembly line of fame if their image is framed the right way.

Suffering and spectacle go hand in hand. The real, wretched experience of day-to-day victimization - what Laura experienced and what JT claimed to have experienced - stands in dramatic tension with the exhausting, "shocking" theatrics that both played up to get people's attention and empathy. Shyness perverts social life, making one's public performance slide into a desperate exhibitionism that approaches the pathological. JT/Laura knew better than anyone the art of hype, and now they're the scapegoat for everyone who has ever needed to invest their feelings into and identify with someone fucked up like them - but who has achieved the holy grail of fame. Take note of the obvious joy that pundits received from unmasking JT - dragging the truth kicking and screaming from the queer shadows with headlines like "He's a She" that have the tone of a transsexual's "real" sex being brutally exposed on Jerry Springer.

JT Leroy was not the first of his kind. Anthony Godby Johnson was a thirteen-year-old boy who was reportedly severely abused and used as a sex slave by his parents and their friends, becoming infected with HIV in the process. He wrote a memoir, A Rock and a Hard Place , which detailed his miserable family life, his escape and learning to love again, and his battle with AIDS. Like JT, Tony also sought free therapy and editorial advice from established gay writers - in Tony's case, Armistead Maupin, who fictionalized his own experience into The Night Listener . In fact, the woman claiming to be his adopted mother had invented Tony, and the ruse was kept going by a coterie of conspirators who felt that America needed a Tony to believe in: he was the product of pure faith. Through its collage of voices and images that never fully add up to a complete picture, Joshua Thorson's portrayal of the case (also called A Rock and a Hard Place ) perfectly captures how any potential real boy that may have existed becomes clouded in an impenetrable miasma of desires and projections.

Tony differs from JT in that he never went in front of the cameras and his youthful memoir was seen as a brave and touching redemption story for the soccer mom set rather than the cutting edge of transgressive literary fiction. His creator was not nearly so bold as Laura, who convinced her sister-in-law Savannah Knoop to dress up and party as JT on numerous occasions. Tony was a shut-in, the best model of victimhood because he spun his abject sickness as noble, inspiring rather than discomforting. But the most important quality that JT and Tony share is that their status as fictional constructs is seen as a vicious assault against the fans who needed their heroes' autobiographies to be true. Whether it be Maupin's community decimated by AIDS who were inspired that a child who had endured as much suffering as Tony could still crack a joke and have hope for the future, or a whole generation of fucked-up queer kids struggling with gender, drugs, mental illness, abuse and poverty who saw in JT how their similar but less spectacular traumas could be redeemed through harshly poetic literature. One can't just be fucked up, but one has to be able to surmount that fucked-upedness just enough to record it in as visceral and affecting a way as possible, creating books and magazines for the people to consume and to identify with. (And then one needs the connections to make a splash). Many are now dismissing JT's fiction because its power depended on its being based on autobiography, the great lynchpin of the JT system. And when the authenticity is removed the whole structure collapses; what was being sold was the vicarious experience of real suffering and not the fantastic use of words that adds up to literature.

Some forms of being fucked up sell better than others. According to Laura, none of this was a joke or a scam, but part of a life of sublimating her identity into fictional creations as a way of mediating her existence in the world: From a very early age she meticulously performed fantasy alternate selves. Cooper, who never met a suffering gay teen he didn't like, couldn't care less about what chain of events might have led a grown woman to write these words and create this persona. We might enjoy reading the saga of JT the ultimate hustler on the page, but God forbid we should be the ones to get hustled - and by a woman no less. Laura's own narrative bears many similarities to JT's, despite the dismissive labels of "middle-class," "middle-aged" and "straight" imposed on her by the press: She is from a broken and abusive home, she was institutionalized, and she lived on the streets of New York and San Francisco before becoming a sex worker (though the phone and the written word were her moneymakers, naturally). But just like with anyone else, abbreviated buzz-words like these fail at taming the messiness of Laura's life experience if her testimony in The Paris Review is to be believed. Heavily involved in the punk scene - she was essentially a lower-middle class Brooklyn Jewish girl passing as an Avenue A skinhead - she realized early on that women were not taken seriously in this macho, authenticity-obsessed subculture. She discovered that if she presented herself on the phone as a boy - especially a British one - she could get close to the men in the scene who seemed out of reach. She took on abused street-kid boy drag in order to penetrate the elite of specific subcultures, and likely had no clue that the marginal, alterna-scenes she inhabited would become such a turn-on for mainstream celebs keen on some slumming, that a friendship with Dorothy Allison would be upgraded to one with Madonna.

We want our suffering young and fresh, as we lust for children in danger. We are obsessed with stories of lost innocence (especially when it has been stolen by adults) and of children who are able to accomplish what we believe was once only possible later in life, whether it be coming out as queer before puberty or being a literary prodigy. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the booming art world, where young artists are being snapped up by galleries straight out of school and touted as the next big thing until someone younger comes around. Without casting aspersions on Ryan Trecartin's considerable talents and energy, I believe the way his career has been framed is an excellent example of this. An anecdote: Dennis Cooper was one of JT's most loyal mentors, and it is impossible not to see much of Cooper's own world reflected in JT's (it has become cliché to note that JT could very well be a character out of Cooper, which I think is a delightful twist). He also authored one of the bitterest reflections on the hoax once Laura had been unmasked as JT. But just a couple of months later, there was Cooper trumpeting the gloriously fucked up universe created by another youthful underground queer boy in the pages of Artforum (where he is a contributing editor): Trecartin was his pick for artist to watch in 2006. His review spills as much ink on Trecartin's traumatic exodus from his home of New Orleans and his "discovery" (an artist showed a curator some of A Family Finds Entertainment posted on Friendster and a feeding frenzy soon followed), as he does on the young man's artwork, and Cooper ends with the lofty phrase: "...the great excitement of Trecartin's work is that it honestly does seem to have come from out of nowhere." The diamond in the rough, and history repeating...

If you still doubt the appeal of the fucked-up boy, consider that JT quickly became whiny, bratty and repellant in his neediness and starfuckery, but that did not turn off many of his phone buddies. It seems he could get away with anything because of his youth and what he'd gone through, everything that is except being unmasked as a fiction. In the end, among many other things, JT was a cartoon parody of an endangered child grown up and gone wild, created by a damaged - and deeply queer - woman who'd seen enough to know what voices have power and cachet in the cultural avant-garde.

JON DAVIES

"We are precious products, all of us." - George Kuchar

CONFESSION:

Excerpts from Laura Albert's interview with Nathaniel Rich in The Paris Review .

Albert: As far back as I can remember, I always had stories. They tended to be about boys who were in trouble. I would tell myself these stories every night when I went to bed. It was like watching a movie. I would rewind it a little bit, then replay it and watch it again to help me fall asleep. Sometimes a story would keep me awake, though, and I'd start crying because I didn't know how it was going to end.

Interviewer: Why do you think your protagonists were boys?

Albert: All the stories I was encountering were about boys. The characters that were allowed to have adventures and allowed to have redemption were boys, from Huck Finn to Tom Sawyer to Oliver Twist to Peter Pan. What were the girls? They were princesses. And I knew that was not my story. I was not a cute little kid. [...]

I needed layers of distance. Being a girl was too close to me. I could never say, for instance, that my mom tried to set me on fire in my room, or that I had to barricade myself in my room because my mom was coming at my door with a hammer, or that I would come to school with thirddegree burns from coffee being thrown at me.

Interviewer: Did those things really happen?

Albert: Yeah. But my selfesteem was so low, I was afraid that if I told someone what was going on, they'd say, Well, you deserve it. Still, I had the fantasy of help. As long as I was different - if I were cute, if I were little, if I were boy, it would be ok. [...]

Interviewer: Had you stopped calling therapy hotlines yourself by this point?

Albert: No, I was still calling them all the time. But then I started speaking with a psychiatrist named Terrence Owens. We had a halfhour phone conversation every day, and I built my life around that. It was the only time I felt alive.

Interviewer: Were you speaking to him as yourself - as Laura Albert?

Albert: No, I called him as a boy named Jeremiah. He was thirteen at the time, and he was from West Virginia. At first I didn't really know much about him. As with my other characters, I wouldn't know who was talking until the person spoke through me. He would reveal himself to me, I would let it unfold, and I would go to that other world, which was much better to me than my own world, which I hated. I never thought, My God, this isn't true. It felt more alive and more true to me than any of the things in my world.

Interviewer: What was the story that emerged about Jeremiah?

Albert: Jeremiah's family was educated and wealthy. His grandfather owned radio stations and telephone towers, and he was a very religious man. His mother was a woman named Sarah, who gave birth to him when she was thirteen. His father was a theologian who came into their home to study with the grandfather and got seduced by Sarah, who was a rebel, trying out her fledgling sexuality. But she was still an innocent - a child - so it was also like a rape. Then her father forbade her from having an abortion, and shortly after she gave birth to Jeremiah, he was taken away and raised in a foster family. Sarah started to work as a waitress and hustled, just trying to survive. She started drinking. When she was eighteen, the state contacted her about giving up her legal rights to the foster family. She refused and her father helped her win her kid back because he didn't like government interference - he was very conservative and antigovernment. So she got the kid back, but Jeremiah, who was four, didn't understand why his foster family had given him up. Sarah told him it was because he's evil. She scared him into staying with her. How could the kid make sense of this kind of betrayal? How do any of us make sense of betrayal at an early age? Every day, on the phone with Dr. Owens, something new from Jeremiah's story would be revealed to me.

Interviewer: Did he ever question its veracity?

Albert: No. He helped me with the feelings beneath it, because it was all very true to me. I just told a story that fit that pain I was in. So Sarah and Jeremiah traveled around a lot -Portland, Seattle, Los Angeles. They lived in poverty, and both of them would hustle -which was true for me at the time. Jeremiah would try to emulate her. It's like how I, as a girl, acted seductively toward the men that my mother brought into the house, not really understanding what I was doing. I'd get raped, but I didn't think of it as rape. I didn't know those terms. I went along with it, and at times, without understanding the

consequences, I initiated it. That's what many people don't understand about abuse. People want to think that the kid is always innocent and angelic, but, I'm sorry, abused children develop survival strategies that aren't attractive. They can be capable of provoking violence, because getting hit feels like an articulation of love. That isn't convenient or pretty, but it's true. That doesn't mean that the kid is guilty - the kid does not understand. That's how it was with Jeremiah. He wanted attention and love without really knowing how to get it. On the street, Jeremiah would call himself Terminator. The name was kind of a joke, because it was the opposite of his actual personality, which was

shy and introverted. Jeremiah liked it because it gave him a sense of power. So sometimes he was Jeremiah, sometimes he was Jeremy, sometimes he was Terminator, and later he was JT. His last name was Leroy, which is the name of a good friend of mine. Finally, Sarah abandoned him in a motel in San Francisco, and Jeremy wanted to commit suicide. He didn't want to go back to hustling or living in the street anymore. He wanted to find a therapist to tell him that he could commit suicide, that he wouldn't go to hell if he did, because he just couldn't take the pain anymore. That was very true for me. I wanted someone to say, ok, you can give up now. I would feel suicidal and I was unable to express that as me, so Jeremy would take over. Jeremy reached out to lots of different people, until one day he found Dr. Owens.

Interviewer: You invented Jeremy, but you say he took you over - as if he existed independently of you.

Albert: It really felt like he was another human being. I'm talking about him in the past tense because I feel that his energy is not the primary force inside me, as it was then. [...]

Interviewer: So you lived in some fear of being exposed?

Albert: We'd talk about it sometimes, but we knew our intent was not malicious, so we didn't feel ashamed. We asked ourselves, Are we making anyone do something they don't want to do? Are we being of service? Are we making people feel good and spreading love? We felt that we were. People responded with great love and great happiness to JT and to his writing. It wasn't like we were spreading some dark thing. [...]

Interviewer: Were your relations with music and film celebrities generally different from those with writers?

Albert: Yes, but for the most part, those star types were approaching me. Or they would mention my work in a magazine article, and then I would write to thank them. I found out that Sheryl Crow had talked about my book on her website, and I was floored. Someone told me that Winona Ryder was into my work, and Drew Barrymore was too, and I was put in touch with them. Lou Reed read the books and he was really supportive. Shirley Manson read about JT in The Face magazine early on, and we saw her play in L.A., and we all had a big pajama party. Shirley was as welcoming to Speedie as she was to JT, which was rare. She wrote a song called "Cherry Lips" based on the character of Cherry Vanilla, from Sarah . We did a huge photo shoot for the icon issue of Pop magazine. I remember Courtney Love told me, You're an iconoclast, JT.

Interviewer: You mean she said that to Savannah?

Albert: No, she said it to me on the phone. And I was like, Wow. I'd pick up the newspaper and things would be referred to as in the "JT Leroy mode." it was surreal. Musicians started to ask me to write stories about them to go with press releases for their new albums. I wrote one for Billy Corgan, one for Bryan Adams, Nancy Sinatra, Bright Eyes. JT was the person to go to if you wanted to be cool or reach the young people. Shirley Manson passed my writing on to Bono, and in an interview with Rolling Stone , Bono talked about how The Heart Is Deceitful [Above All Things] was blowing his mind. We met him, and he was wonderful to all of us. The director Allison Anders read Sarah and passed it on to Madonna, and she told me that Madonna was reading it. I was in Florida, swimming in the pool at my grandma's house, and I was thinking, My God, Madonna's in my world. It was an incredible feeling. I knew that if I met her, I would not register on her screen at all. So to know that she was in my world - it shouldn't have given me this feeling of elation, but it did. I just remember I was swimming back and forth in the pool. It was like running over a joyful spot that gave me energy. She's in my world, she's in my world, she's in my world. But Madonna and I never had much to say to each other - it was more a vanity thing. She once sent me a bunch of Kabbalah books. I kept one and I sold the others. I needed the money more than I needed the Kabbalah.

Interviewer: How would you feel when you watched Savannah out in the public as JT?

Albert: I wasn't watching Savannah, I was watching JT. It was a great relief because JT would leave me and enter her. I felt amazement, elation, pride. People would line up all day to see him - he'd get the rockstar treatment. They had to get us security guards because all these people just wanted to touch him. I remember once we went to Sweden to do a reading, and people were bowing down and kneeling before JT. It happened spontaneously, and it was beautiful. And I was there standing on the side, asking people what brought them. They would always talk about the books. I could get what I wanted - connecting with others - without having to be the focus of attention. [...]

Interviewer: How did you explain JT's feminine appearance?

Albert: Savannah was really beginning to embrace JT by this point. Even her body had changed. It became very masculine, her period stopped, her breasts got smaller. At the same time, JT was transforming himself into a woman - it was his truth. He started talking about getting hormonal treatments and having a sexchange operation. [...]

Interviewer: What did you foresee happening to JT? Did you expect him to grow up and continue writing?

Albert: I always felt like JT was a mutation, a shared lung, and for me to become normal I'd have to breathe on my own. Originally I felt that he might die of AIDS, but that's not in any of the books. I didn't deny the rumors, but I never made any statement intended to further JT's popularity by claiming he had AIDS. I remember one day ten years ago I thought, he will die this weekend. I went into deep mourning. I was physically sick. But JT didn't want to die, and I couldn't let him die. I felt that if he died, I would die.

Interviewer: When the New York Times told you they were going to expose you as the author of the JT Leroy books, did you deny it?

Albert: I said, I don't know what you're talking about. I wasn't ready to admit anything. I published everything as fiction. JT was protection. He was a veil upon a veil - a filter. I never saw it as a hoax. It was bizarre, when the articles came out, to read these interpretations of what we were doing. I was holding on for dear life. One public relations guy yelled at me over the phone, You're a fake! You're a phony, fuck you! The therapist in my son's school said to me the other day, You know, from what I can see, they're accusing you of being a great writer. But you wouldn't know it. You'd think it was drugs, or a sex ring.

Interviewer: Did you - or do you - feel any shame about misleading people who believed in JT?

Albert: I bleed, but it's a different kind of shame. I'm sad I was so injured. Many people were inspired that someone so young could write what I was writing. JT is fifteen years younger than me. All I can say is I am sorry if people are disappointed or offended. If knowing that I'm fifteen years older than Jeremy devalues the work, then I'm sorry they feel that way. Everything you need to know about me is in my books, in ways that I don't

even understand. I think some people take it for granted to be acknowledged and not overlooked. My experience was to be completely ignored and disregarded and disdained. That's what I write about. One thing people often comment to me about the characters in JT Leroy's books is that they strive for goodness, even in a world where all their experience contradicts this. I feel that desire is essential to my story as well. When I would reach a point where I wanted to commit suicide, something gave me hope. This hope is in the books too - and of course the ultimate hope is that I can reveal myself and you won't go away. [...]

GOSSIP:

"[JT is] just a wig and sunglasses floating around a dizzying production of narrative. And perhaps no other culture has valued the contrived happy ending as much as ours. For all its abuse and kinky sex, the JT story is really just another heartwarming rags-to-riches tale for the punk generation. But what if America isn't really the sort of place where a street urchin can charm his way to the top, through diligence and talent; what if instead it's the sort of place where heartwarming stories of abused children who triumph through adversity are made up and marketed?" - Stephen Beachy

"One afternoon in 2001 my phone rang and on the other line was a hesitant, tiny voice with a Southern drawl. I was unlisted, but JT/[Laura]Albert had found my number somehow. We talked for three hours, and as others can attest, the experience of talking to a young boy who had worked as a truck stop hooker was eerie, fascinating and addictive. He recounted his crazy life and adventures, mentioning that everything he wrote was autobiographical, and furiously dropped names of celebrities. He said he had just gone to San Francisco's swanky Charles Nob Hill restaurant with Gus Van Sant, where they got drunk and threw food around. Albert gave great phone. [...] 'I see JT as an elaborate nom de plume,' says former New York Press editor [John] Strausbaugh. 'Sort of a 21st century George Sand. Here's this middle-aged woman who's not getting anywhere as a writer. She reinvents herself as a girly boy and becomes a huge success. On whom does that reflect more poorly, her or all the rest of us?' - Jack Boulware

"There was something strangely seductive about that breathy voice on the phone. He was fun to talk to; the sheer magnitude of his self-absorption was entertaining [...] I can't, of course, speak for Madonna or Winona Ryder, but I was snookered by something JT inspired me to feel about myself. Sure, there was the general entertainment value of listening to stories about the train wreck that was his life. Even as pure fiction they were fascinating. But more than that, talking to JT made me feel good about myself. It might have been because he gave me the opportunity to feel completely sane and secure. It might have been because I was flattered that the same person who whiled away hours with Margaret Cho also seemed to enjoy talking to me. But mostly it was because whoever he was, he seemed so genuinely in need of advice and assistance. It feels awfully good to be needed. It feels good to think of myself as someone so generous with my time that I was willing to devote hours of it to a fucked-up near stranger. That's why I can't possibly be angry at having been taken in. I got as much out of it as he did." - Ayelet Waldman

"LeRoy's books call like sirens to emotional tourists looking to vacation in someone else's torment. Abuse, gender confusion, abandonment, prostitution, addiction - all the sensationalistic obsessions of our era, wrapped in one neat adolescent package. If hustling taught LeRoy how to sell his physical self for self-preservation, therapy showed him how to mine the ore of his personal life, how to use his realness both as a seduction tactic and as a shield. [...]

All of this slipperiness has led some early supporters to wonder if they've been played. As [Mary] Gaitskill put it, 'It's occurred to me that the whole thing with Jeremy [J.T.] is a hoax, but I felt that even if it turned out to be a hoax, it's a very enjoyable one. And a hoax that exposes things about people, the confusion between love and art and publicity. A hoax that would be delightful and if people are made fools of, it would be OK - in fact, it would be useful.' [...]

Gaitskill says she took an interest because 'he's one of the smartest people I've ever talked to in my life. It's an uncanny sort of intelligence, like he can read people without meeting them. ...I sometimes got this image of him as a glistening gossamer net moving in response to sound, thought, feeling, any kind of stimulus imaginable.'" - Joy Press

"[Laura] didn't have to con me to get me to pay attention to her writing. But by portraying herself as the Little Cripple Boy, who'd choke back the tears as he asked me for a match, she set up the dynamic that determined the rest of our relationship: Don't expect anything from JT - he's too fragile. Don't tell him to not be an asshole - he can barely get up in the morning. Never refuse a request, no matter how crazy - he's never had anyone he could count on in his life." - Susie Bright

"'This charade is unfortunate and cruel for gay and transgender writers who fight over many years to get into print,' said Charles Flowers, director of Lambda Literary Foundation, an organization that promotes LGBT writing. 'It's particularly cruel for people who read the work hoping to find an image of themselves or to have their experience reflected back.' Flowers believes the LeRoy debacle will make it harder for real transgender and gay writers who have survived difficult circumstances to get their work published." - Patrick Letellier

"It turns the redemptive quality of a lot of writing into a total farce." - Michelle Tea

FURTHER READING:

Stephen Beachy, "Who Is the Real JT LeRoy?: A Search for the True Identity of a Great Literary Hustler." New York Magazine October 17, 2005.

Jack Boulware, "She Is JT LeRoy." Salon March 8, 2006.

Susie Bright, "You're No J.T. Leroy - Thank God." Susie Bright's Journal January 8, 2006.

Dennis Cooper, "JT Leroy and the Surrounding Area." Dennis Cooper's Blog January 13, 2006.

Tad Friend, "The Ghost Writer." The Independent March 24, 2002.

Anthony Godby Johnson, A Rock and a Hard Place: One Boy's Triumphant Story . NewYork: Crown Publishers, Inc. 1993.

JT LeRoy, The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things . New York: Bloomsbury, 2002.

JT LeRoy, Sarah . New York: Bloomsbury, 2000.

Patrick Letellier, "JT LeRoy hoax angers LGBT Fans, Writers." Gay.com January 12, 2006.

Joy Press, "The Cut of J.T. LeRoy: How a Teenage Hustler-Turned-Novelist Built a Celebrity Support Group." The Village Voice June 13, 2001.

Nathaniel Rich, "Being JT LeRoy." The Paris Review 178 (Fall 2006), 145-68.

Warren St. John, "The Unmasking of JT Leroy: In Public, He's a She." New York Times January 9, 2006.

Ayelet Waldman, "I Was Conned by JT Leroy." Salon January 11, 2006.